David Lynch’s film interpretation of Frank Herbert’s series of Dune novels was released in 1984. I watched it in the Savoy cinema in O’Connell Street in Dublin. The exact day and date I no longer remember. With many of the most important changes in life, they have already happened some time before you realise.

The Savoy was one of the

two main cinemas in O’Connell Street, the Carlton was across the road. The

Savoy 1 was possibly the biggest screen in Dublin at that time. The Savoy 1 or

the Adelphi 1 in Middle Abbey Street were the places you wanted to see a movie

if you could.

Dune is rightly considered, as

Chris Rodley observes in faber and faber’s Lynch on Lynch ‘…one of contemporary

cinema’s most striking examples of the chaos that can ensue when world’s

collide: when personal vision meets mega bucks, small meets large, naivety

meets reality and private meets public.’ It was the second of two studio

films Lynch would direct including The Elephant Man but this one, Dune, was for

the family whose very name meant overblown and giant budgets, Dino and Rafaella

De Laurentis. It would be the last film of that kind Lynch would make. He went

back to his home of indie film-making after having such a difficult time that

it has been suggested as the reason he came up with the wonderful Angriest Dog

in the World cartoon during this period. This was a cartoon about a dog who was

so angry that it was basically frozen eternally at the end point of its chain’s

tension in a perpetual growl. It featured the same terribly frozen four panels

every time with only the text changing. I should acknowledge; however, that he

denies any causal connection between the two. And maybe you should trust him.

I do like the fact that Lynch on

Lynch also nods to the possibility that he may have been tired of being a

starving artist and be attracted to the money that was on offer. That’s a theme

that I believe we will return to throughout this series.

I saw Dune with my father as I

saw most films back then at the age of twelve. After the movie finished we sat

in silence. We waited the twenty minutes for the next screening and sat through

it again. It was a wonderful feature of going to the cinema in Dublin back then

that they very seldom kicked you out if you wanted to stay and watch the movie

twice or even three times. you could see the 2, 4, and 6 o’clock showings if

you wanted. Dad and I often watched a film twice, sometimes because we missed

the first couple of minutes of the movie due to his dreadful time keeping but

that was really just an excuse. So it wasn’t unusual for us to watch the movie

again straight away but it was unusual for there to be no discussion about it.

My Dad was not much of a talker but we would always share a smile or a grin and

a ‘what do you think, will we watch it again, dinner wouldn’t be ready till 6.’

Not this time.

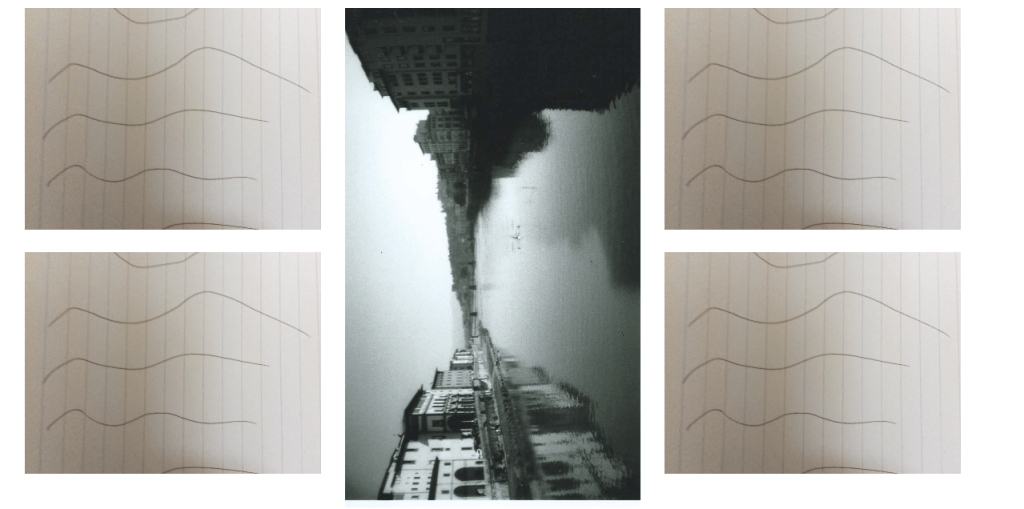

This afternoon we sat in stunned silence. I am sure that we stared at the screen until the movie was over for the second time and then left in silence and walked home down the grey quays of the River Liffey without a word. Again, this was unusual even for us. We hardly ever talked but we did talk about the movies we had seen. That was our oasis, whatever was blocking communication between us but we were not ready to talk about this movie. Or perhaps it would be more honest to say I was not ready. I was in such a stunned state I was not capable of seeing if my Dad was equally affected or not.

In German it is called

‘unhomlich’ in English ‘uncanny’. I prefer the German word though as it is more

descriptive of the feeling. Un-homely, away from the usual. That was the state

in which I spent the following days. I had been shaken out of my homely state.

I didn’t know it at first, that took time to bubble to the surface of

consciousness but Dune had changed pretty much everything. The world was not

the same anymore. I had not understood that movies could be this, whatever

this was. Whatever this was I liked it, no was compelled by it, needed more of

it. I just needed to figure out what the hell it WAS.

Dune was released the same year

as Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. That’s a good movie too but they are a

good contrast. I enjoyed the Spielberg film but I recognised that Dune was a

completely different species. And I knew which pack I wanted to run with.

Still, Dune was in many ways

alien to a child’s mind trained by American mainstream cinema. There were so

many things wrong with it. It was completely bathed in a weird pink light,

there were European Actors using their own accents, the soundtrack was an

unholy mix of soft rock giants Toto and Brian Eno, it was sci-fi and action but

the action was muted and the future it depicted was more biological than

technological. Lynch himself talks about that as slightly disappointing,

slightly sad. He likes big machinery and smoke producing factories but he saw

that they were dying out and that is reflected in Dune but as I mentioned in a

melancholy way I think for him at the time.

There were children killing

people and holding long knives in spiritual ecstasy, that second moon that was

so important was clearly MEANT to look more like a pulsing egg thing than a

rock, the Baron Harkonnen’s doctor spoke like his dialogue was written by

William Burroughs ‘Put the pick in there Pete and turn it real neat.’ Speaking

of his passion for the Baron’s beautiful skin diseases.

It is noteworthy that it was at

this time that Lynch had begun his photographic series of dissembled animals:

his fish kit, chicken kit etc. He was photographing the corpses of animals he

had cut up and labelled like a child’s model kit.

And Dune was most disturbingly,

for me at that time, a completely sincere and serious film and a film about

consciousness. The Spice Mélange, the substance over which all the battles are

fought, is an all-purpose psychedelic and fuel. Control of the Spice is control

of the universe, though that control comes with the certainty of horrific

mutation. Travel happens essentially in the mind and the two warring families,

the Harkonnens and the Atreides basically represent lower and higher

consciousness respectively. The Harkonnens are bestial, brutal, uncontrolled

and interestingly only seem to eat meat often alive; the Atreides are high

minded, noble and I think the one instance shown of any of them eating is of

Paul eating the Spice. Paul Atreides, the young hero of the film, is an

honourable and since young noble who must awaken to his destiny in order to

create a future of peace, justice and order.

I now see Lynch’s oeuvre very

much as being about the barriers to contact with a creative consciousness. In a

way he makes films about the state of mind of the artist and the process he has

of setting up conditions for making art.

The place Paul Atreides goes,

that establishes him as unique, a messiah figure, is so similar, figuratively

and visually, to the place that can’t be explained where so much of the most

recent Twin Peaks TV series ‘takes place’. If it is a place.

David Lynch,

as his history with Transcendental Meditation, shows is a man very concerned

with things that block consciousness and a conviction that things that block

are evil.

At the

time I first meet this film I had a relative who I will not name because they would

have been ashamed of this story. They shouldn’t have been but they would have.

The only reason I’ll tell this here is because the person in question is dead

now but I will keep it anonymous out of respect.

This person lived with their mother very close to us. So we were over there a lot. They had a serious anxiety issue and like many people then they were prescribed Valium and like many people they became addicted. Of course that caused great shame and more anxiety and created a vicious spiral. One of the things that they tried to help alleviate their suffering was Transcendental Meditation, TM.

When we

children were around the house sometimes we were told that the living room was

off limits because this person was doing their TM. Being children of course we

found ways to open the door and sneak a look in there and see them slumped in a

chair, completely zonked and drooling.

We just thought this was amazing.

There was no shame to be detected there for us. We were stunned by the power of

this thing called TM. We were told that people who practised TM were given a

mantra, a word or a phrase, that they used to help them get into a deep state

of meditation and relaxation. So of course what we heard was that if you said

this word around our relative they would instantly go into a state of deeply

floppy dislocation. We figured this would be something ‘out there’ and unusual

and I feel sorry now for my poor relative as we kids threw strange words

randomly into conversation and watched with little expectant faces and then

spreading disappointment when they failed to instantly dissolve in saliva

dripping Zen.

What I’m saying here is that the

conscious discussion of human consciousness was lost on me at twelve but the

impact was there. I understood that this was something new in my experience. I

knew now that films were capable of doing things that I had not known they

could before. They could be about things that were compelling to me even if I

didn’t exactly understand what those things even were. As much as I enjoyed

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and its ilk, Dune was something more

important. And that was a value judgement, possibly the first that I clearly

made for myself when it came to art.

The main problem for the twelve

year old me was that I wouldn’t have ready access to Dune type films for quite

a long time, so much so that I think I believed it might just be a

strange outlier, an anomaly, the one and only movie that had that quality.

I didn’t think about directors

then or auteurs. I was still young enough to sort of believe films happened by

magic of some kind. I certainly didn’t believe they had anything to do

with me or my world beyond my being a spectator. I certainly couldn’t accept

that I or anybody I knew could ever make one any more than I could make a

sunset. I was raised Roman Catholic but I think that I never believed in any

god except in the way you believe 2 and 2 is 4 as a child because adults tell

you it’s so. With Dune, I started believing in art in a way I could never

believe in a deity.

I am grateful, in fact, that the

first David Lynch film I saw was this one and at that age. A different one at

that age would probably have been too much for me and if I had seen Dune for

the first time say four or five years later it may well not have cut so very

deep. Lynch’s next feature would be Blue Velvet and I was not ready for that. I

still wasn’t quite ready for it when I saw it in a double-bill with Eraserhead

in the wonderful Academy Cinema some time in the 1990s.

‘I see my fears double-exposed

with the images on the screen.’ Lynch discussing his feelings leading up to the

end of making Dune.

Fear as I

chanted at the beginning of this episode is the mind killer and fear was a huge

part of my life then. I lived in a very small territory between Arbor Hill and

O’Connell Street on one side and Phibsborough on the other and it was a dark

and rough time, dark and rough enough for me anyway.

This was a

time when we were beaten with canes and leather straps in school, made to kneel

on wooden floors facing into a corner with arms out cruciform and routinely

humiliated in other ways. There was a lot of casual violence to be seen on the

walk from home up and down the quays to and from town: fights outside pubs of

course but violence against sex workers, assaults of all sorts, these things

were almost routine. I certainly didn’t find them unusual; they were part of

life. Bare arses rising and falling out of the overgrown grass of the Croppies

Acre before I really understood the facts of life. I understood some twisted

facts of a situation that normalised darkness and put light in the shade. I

understood that if the British board of Censors certified a film as 15s and

Ireland certified it as 18s- that meant sex. If it was the other way around,

18s in Britain and 15s in Ireland, that meant violence. You learned these

things and understood what they meant about the world you lived in, the values

of the society you were from. It’s always clear, even if it’s hidden.

Dune might

have been the very first moment that I even began to realise that fear might be

a problem I would be dealing with for the rest of my life and how I dealt with

that fight might largely define my life.

The films we

will talk about on this podcast will be the ones that have helped me most with

that. And other things.

There is a

kind of spiritual battle in Dune.